- Home

- Elgin, Suzete Haden

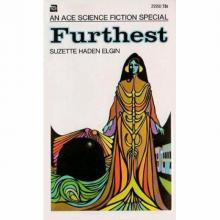

Furthest

Furthest Read online

Furthest

SUZETTE HADEN ELGIN

When Coyote Jones visited the planet Furthest, he was strictly limited in the areas he could see. He could move freely within the city where he worked, and in a couple of smaller towns, but everything else was forbidden—especially the giant dome that covered a city called Ta Klith.

Naturally that was the first place he went, when he’d eluded his watchers.

He reached the dome safely—only to be astounded when he found nothing inside. No city of three hundred thousand people as the Furthesters had claimed, only a bare expanse of rock and water under that huge dome.

Then why were the Furthesters hiding it? And… what deeper mysteries remained on this enigmatic world?

SUZETTE HADEN ELGIN was born November 18, 1936, in Louisiana, Missouri and grew up in the Missouri Ozarks. Now living in Southern California with her husband and four children, she has a B.A. in French, a teaching credential, an M.A. in Linguistics, and is now finishing up her Ph.D. in Linguistics, specializing in Poetics and Navaho Syntax.

“Where jobs are concerned, I’ve done almost everything: translating, interpreting, bilingual secretary, modeling, teaching, and singing. I’m old enough that the first singing I did was the antique torchsinger lean-on-the-piano-in-a-red-velvet-gown stuff; after that, when folk music came back, I worked the coffeehouse circuit And I write.”

FURTHEST is her first novel. Ace Books has previously published her novelette For the Sake of Grace in WORLD’S BEST SCIENCE FICTION: 1970 and a novella, THE COMMUNIPATHS, as half of an Ace science fiction double.

Furthest

CHAPTER ONE

“A secret is like a small child; the more you do for it, the more of a nuisance it becomes. Before you take upon yourself such a burden, consider well—the chances are that unless you take elaborate pains to conceal something it will never be noticed.”

(from the Devotional Book of Tham O’Kent)

He had to sit very still. The slitherboat was not an easy craft to manage, and the beginner was likely to end up in the water almost at once, with no hope of ever getting on the bloody thing again. So far as Coyote knew, of course, he was the only beginner.

That was a bit hard for him to understand. But then almost everything on this planet was hard for him to understand.

He had put in a lot of time preparing for this night, and had gained himself a reputation as a harmless idiot offworlder who actually found it amusing to putter around at night in a slitherboat. The idea had been that when he got to doing something more than just putter, nobody would pay any attention to him, and he sincerely hoped that would turn out to be an idea with an accurate base.

He had stopped using the miniature paddle and was letting the current carry him, seemingly aimlessly, knowing he could count on it to head him in the right direction eventually, and he was digging the view around him while he drifted.

It was spectacular, you had to give it that. By day there was nothing to see out here, and the land spread out in all directions, the same dull gray color, unrelieved by tree or grass or any mark except the bluffs and spurs that loomed up here and there. If you could call it land, that is, because strictly speaking there wasn’t much land there. It was a sort of rock net, somehow holding together the millions of flowing streams that were the real stuff of the planet. Sometimes there would be a strip of the gray rock as much as ten feet wide, but not often; the streams were everywhere, twisting and winding, honeycombing the rock so that the actual surface was almost entirely water. The streams themselves were gray, too, because they ran through the gray rock, and none of them more than two feet, perhaps in rare cases three feet, in width. By day it was all gray, as far as you could see, and one of the ugliest sights in the universe, to Coyote’s way of thinking.

At night, though, it was different. It was different and beautiful and splendid, because that same gray water bore in it a small creature invisible to the naked eye, but fluorescent, and multicolored, and in the dark the rainbows flowed everywhere in a glory that Coyote knew he was never going to be able to describe to anyone who had not actually seen it.

There was not an inch of the water that did not teem with the spangled life, not an inch that did not dance and pulse with red and green and gold and a deep soft blue. The little geysers that went unnoticed in the daylight, not very high and not very impressive, were incredible in the dark, throwing fountains of color like flung fireworks into the air. They went off all around him, apparently random, although he knew there must be a pattern to them. And the streams poured magnificently stippled and pied down the sides of the bluffs and the pillars of rock, leaping from face to face and throwing bridges of brilliant color across the sky.

Coyote could not imagine tiring of it. He could have sat and watched it all the night long. But he sat there all alone. On any other planet of the Three Galaxies such a display would have been crowded with people, its magnificence would have drawn eager watchers not only from the planet itself but from all the planets of the Tri-Galactic Federation. Not here. In the course of more than twenty nights that he had spent out on these… What could you call them? Deserts? Could there be a desert of water?… these whatevertheywere, he had seen another living being only once, moving purposefully on a slitherboat and not even looking at the rampant beauty around him.

He had asked RK, the boy who worked for him, why no one ever went out to watch the water at night, and had received a blank look of incomprehension. “Watch the water? Why should anyone want to do that?” RK had said flatly.

Perhaps these people were color-blind. Perhaps familiarity bred contempt, even in the face of all this. But if familiarity was the problem it seemed that the children and younger people, to whom all this display would be more new, would come out at night to enjoy the view. And they didn’t. No one came, except himself, all alone on the cursed bare flat sliver that they were pleased to call a boat.

At first he had continually fallen off, since there was nothing to hold on to and not even a ridge to give you purchase. The slitherboat was a lot like a surfboard, except that when you fell off you didn’t go into open surf but smashed against the rock walls of a stream not much wider than you were. And every time he fell off he had had to climb out and race madly along the web of rock until the slitherboat reached an abrupt turn that would slow it down enough to let him grab it. At such times he had been delighted to find himself alone, since he would have been a hilarious spectacle for anyone watching.

“Do your people ever fall off the slitherboats?” he had asked RK, and gotten that same strange look. “Why would anyone fall off a slitherboat?” the boy had asked, as Coyote would have asked, “Why would anyone forget to alternate left and right legs as they walked?” Such a question could only mean that everyone rode the slitherboats from infancy, that they were as much an automatic part of bodily motion as walking or running, but if that was the case, when did they ride them? Where did the children go to learn? He had never seen anyone riding one, except that one lone man, and he had never seen groups of kids going off to practice together. When and where did it happen? Or was the “obvious” explanation entirely wrong to begin with?

There was a faint chime in the air beside his head then, and he gritted his teeth and tried not to move, since that was the proper way to handle the situation. But he couldn’t stand it; when he felt the little feet on his shoulders, and the tiny hands gripping, he gave in as he always did and started trying to brush them off. And of course the instant he did that the two that had been on him became twenty, or a hundred, and the air around him was alive with the soft sound of a multitude of incredibly small high bells.

Coyote shuddered, cursing himself for drawing the crowd with his thrashing around, knowing that if it happened again he would

do exactly the same thing.

The jeebies were a lot like bats, except that they were bigger, standing perhaps a foot high and having a wingspread of better than three feet. And they were completely transparent, which was certainly different. In the daylight you could sometimes see them, faintly, against the background of gray; but at night they were as invisible as the air, and they came out of nowhere, each one making the tiny chiming sound that functioned like the squeaking and screaming of bats but was definitely a hell of a lot more attractive. And the jeebies, unlike bats, were friendly—so damned friend.

RK had told him over and over. “If you just hold perfectly still, Citizen Jones, if you just don’t move at all, one or two of a flock will come and check you out and decide you’re boring and move on. They just like to pat you a little and find out what you are like, and they can only do that by touching you, you know? Because they’re blind.”

“Don’t move at all, huh,” Coyote had repeated after him. “Sure. Something that feels like a little man a foot tall climbs all over you patting your cheek and rubbing your back and making tinkling noises the whole time, and you just don’t move.”

“Well,” RK had said reasonably, “if you don’t move they will go away. And if you start moving they will get excited and call the rest of the flock. So not moving is best.”

RK was absolutely right. Not moving was best, and it was stupid to move, since the little beasties were completely harmless. But he had done it, and now he had a flock following him, clustering on his head and shoulders, crawling down his back and over his arms and legs, chiming and patting and rubbing.

And he was just going to have to put up with them all, he knew that from experience. It would be a long time before they got tired of investigating him and took off for wherever it was they came from. Grimly he took his paddle from its loop on his back and began to make what he hoped were inconspicuous adjustments in the course he was taking, reminding himself that no matter how incredibly much activity was going on around a man who had drawn a flock of jeebies it was all invisible. Nobody knew but him.

He had no idea, of course, just how closely he was being watched. Or for that matter if he was being watched at all. It would have been easy to assume that he was just out here in magnificent isolation, no one aware of him in any way, since that was the way things looked. But he knew better than to jump to any such conclusion. For all he knew a giant radar somewhere was tracking his every movement. For all he knew a group of men sat hunched over a screen watching everything he did as if he were a threedy program being played for their benefit. He didn’t know. Certainly these people should be capable of an advanced technology; on the other hand, since they never left the planet and almost no offworlders ever came in, it was possible that they were retarded in technological development or simply did not consider such an application of it worth their time. In the six weeks he had been on Furthest he had seen no sign, none, of any sort of surveillance equipment. But the chances were very good that if he had seen it he would not have recognized it for what it was, so he was completely in the dark.

He was operating on the hypothesis that he had been watched, probably very closely, when he first began these night jaunts, and that someone somewhere probably still checked on him from time to time, but that by now they—whoever they might be—had accepted him as a harmless nut glomming their scenery and not requiring any great amount of attention. If he was right, and that was by no means sure—and if he could refrain from doing anything unusual that would attract attention (and since he had no idea what would attract attention, that wasn’t very sure either), and if it didn’t just happen to be time for a regular monitoring check on his activities, he might just come out of this all right.

He sure as hell had to do something. Six weeks, and he hadn’t learned one thing. And his license to remain on this world had an eighteen-month limit that might turn into eighteen hours on him any time.

He had gone quite a distance now. The little boats were like twigs on the water and the currents strong, and two hours would take you a very respectable number of miles. You’d have to hike back, of course, since those currents weren’t going to obligingly turn themselves around for you, and the paddles were no use against the force of the water, but at least one half of any given journey would be pretty rapid.

Off to his left he saw what he was looking for. Now he would really have to be careful, and to his relief the jeebies were beginning to tire of him. He could do without their distraction now.

He turned the slitherboat, not directly toward the black bulk he was aiming for, but on a meandering course calculated to get him to it without giving away his purpose. He wanted to allow plenty of time for a police-copter to appear and warn him off, or whatever it was that might be likely to happen to a trespassing outworlder, before he actually found himself beyond the point of no return on this excursion.

The looming black was now perhaps five hundred yards away, and except for the light from the fluorescent water he would not have been able to see it at all. It had no lights, no markings, nothing to warn anyone off. He supposed it must have the regulation aviation beacon on top, but it couldn’t be seen from the ground in any case.

He was very close now, almost upon it, and nothing had happened yet. He wondered what the penalty might be for breaking into a forbidden city, and decided he didn’t want to know. The time for worrying about that was long since past.

He had found the fork made by four streams that he used as a marker. There was a low rock spur on his right, and he reached out for it, using it to brake his motion, and he pulled the boat hard against the rock. It made a scraping noise, but he could always tell the city fathers, if they came running out to investigate, that he had fallen off. Or that he had had to take a leak. Or that he was lost. He stepped off, or more properly wiggled off, the slitherboat, and lashed it to the rock with an elastic loop.

Now came the tricky part.

Strictly speaking, what he was about to do was probably suicidal. This citydome was forbidden to him, he had been told so kindly but firmly. He was allowed to move freely within the city where he worked, there was a small town on the other side of the planet that he was free to visit, and there was a single village, rather near the city, that he had been told he might enter. Except for that, everything was forbidden—including this dome that covered a city called T’a Klith. But he had found a way in. He hoped.

There was a fissure on this side of the dome, one of the countless streams of water, and it flowed under the edge. Now presumably all he had to do was slip into that stream, wearing his diving gear, and swim right under the dome wall into T’a Klith. Presumably.

There were a lot of other things that might happen. The stream might narrow to six inches and he would get stuck, unable to go either forward or back, and he knew what would happen after that. There might be an electric grid beneath the dome, set to trap just such critters as himself, that would fry him when he touched it. There might be great motors, or exhaust fans, or disposal chutes, any of which he would swim blithely into without finding out in time that they were there. There might be a welcoming committee at the other end with unpleasant implements reserved for nosy offworlders who broke trespass laws.

Those were just some of the things that might happen. He could think of worse. And then there was the possibility that was prompting this whole venture, i.e., that he would be able to make it down the stream and into the city, pop his head up unobserved for a quick look, and get out with a whole skin and whatever information he could gather in the minute he would dare allow himself. It wasn’t really likely that that was what would happen, since there was something very fairytale about the concept of a city that was at the same time forbidden and unguarded, but he was going to buy the fairytale for the moment. He really had no choice. He had to have something to report pretty soon or even his ordinarily resilient conscience was going to start bothering him.

He explored the water carefully with one hand, trying

not to touch the sides of the walls, on the offhand chance that by not touching the rock he would fail to activate any alarms or traps. It seemed to be a wide enough channel, maybe two feet across as it went under the dome.

He checked the straps on his airpack, pulled the waterhood over his head, and snapped it to his wetsuit. RK had laughed at him for insisting on the cumbersome wetsuit, but had cheerfully accepted his explanation that he would get pneumonia if he kept falling into the water in his ordinary clothes.

Now. He waited for one last moment. Now was the time. Now was the time for the flyer to blast out of the air and order him up against the wall. Now was the time for a lawrobot to appear and shoot a hole through him. Now was the time for the giant loudspeaker to open up and order him away. Or something.

Nothing happened. A jeebie chimed, somewhere off to his right. Except for that, all was silence and color and silence. Apparently nothing was going to happen to keep him from having to go through with this. He shrugged, and snapped the last snap on his gear.

Under the edge of the dome the water was colder than outside, but it wasn’t uncomfortable. The current rushed him through the blackness, the channel narrowing not at all, the total dark unbroken. It was completely and unendingly weird, and he resolutely refused to think. Whatever it was that was going to happen, it would happen, and he would deal with it as best he could. For the moment he would just float. Period.

And then, about the time he had begun to think in spite of himself, he was out, past the other side of the dome, and he barely managed to catch a spur on the rock wall and keep himself from being swept right out beyond the edge into the city.

Very carefully he edged to the rim, clinging to the wall of the stream, and exposed just his eyes. Then he put his whole head out and took a long, long look, turning from side to side, unable to believe it. And finally he went back the way he had come, unlashed the slitherboat, and headed for home, numb.

Furthest

Furthest