- Home

- Elgin, Suzete Haden

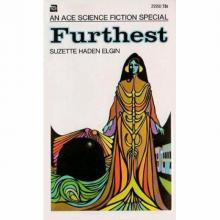

Furthest Page 10

Furthest Read online

Page 10

Coyote stoodup.

“What I am about to do,” he said, “is clear up some thousand-year-old misunderstandings. Come along, though, Bess, and let’s get RK. I want him to hear this, too, and I see no reason for doing it all twice.”

CHAPTER ELEVEN

“to have lain with you, beloved,

is to have known

how the sun feels, rising…

(Anonymous)

Coyote found RK already awake and dressed and busy with breakfast. The boy showed the strain of the previous night. His hands trembled and his lips were tight with the effort he was making not to show his distress. He looked up at Bess and Coyote, one swift bitter glance, and then dropped his eyes at once and refused to look at them again. “RK?”

“Yes, Citizen Jones?”

“I want you to bring all that stuff over here—that’s right, man, just bring it along. Fruit, bread, cheese, coffee, that’s plenty for breakfast. No elaborate carryings-on with paté of waterweed or anything like that are necessary, okay?”

“It’s no trouble,” RK said. “I’d rather do it.”

“And I’d rather you didn’t,” said Coyote firmly. He went over and gathered the food up on a round blue tray, took RK by the arm, and moved both to the table.

RK sat down, sullen and grim, and stared at his plate, and Coyote really didn’t blame him, Last night’s antics had been a little much for one young over-disciplined uptight kid. Things weren’t going to get any better for a while, either.

“RK,” he said, “I’m not going to say I’m sorry about what happened last night, because it would be a bloody lie. What I am sorry about is that I had to be so rough.”

“It’s all right.”

“It’s not all right,” said Bess, “and you know quite well it’s not. You must quit posing, Ahr, and learn the virtues of honesty.”

“You dare to talk to me of virtue!”

Coyote took RK’s credit disc and held it up.

“Look here, RK,” he said. “I’ve got something of yours. I’m sorry I had to take it without asking you, but you wouldn’t have given it to me, you know.”

RK stared at the disc and then snatched it from Coyote’s hand, his face flaming, and pushed his chair back from the table and stood up.

“Now that’s too much,” he said, fairly spitting his words at them. “You’ve gone too far, Citizen!”

“And so? Are you going to call the police, RK, and complain to them that you’ve been robbed?”

“You know I can’t! Because of her!”

“Then you might just as well sit down and listen to what I have to say. I did what had to be done. I didn’t like doing it, but I did it. I’ve read the introductory portion of the Manual for the Training of Mindwives. I’ve seen your Book of the Holy Path. I know what Ahl Kres’sah means. And you have your property back once again. These are accomplished facts, the situation is as it is, irrevocably, and there is nothing to be gained by your stamping out of here.”

“I won’t listen to you, Citizen,” RK hissed. “You are a common criminal, a thief and a fraud and a bully—and worse. I’m leaving this place, right now, and I’m not coming back.”

“I can make you stay,” said Coyote calmly.

“You would do that?”

“I would because I must,” Coyote said. “I would and I will. Either you sit down and listen, as contemptuously as you like, but willingly, or I force you to sit down and listen. That’s all the choices you have.”

“You are—”

“That’s enough, Ahr,” said Bess. “You will hear him out before you spew any more of that sort of thing. Sit down and hold your tongue.”

RK sank down, beaten and seething, in his chair. Coyote took bread and cheese from the tray and waited a moment, giving the boy a little time to recover before he began to talk. The cheese was revolting, having been made from the milk of some mysterious animal on a planet that went by the charming name of Wall-Hole, but it was all there was out here in the fringes, and if you wanted cheese you ate it, and that’s all there was to it. He cut a wedge of it, tore off a chunk of bread, and chewed a generous bite of both, feeling the bubbling of RK’s mind and astonished at the viciousness of it. The boy was really furious, and it was not all pride.

“Well, get on with it,” RK said. “Enjoy yourself.”

“I don’t know how to begin,” Coyote said.

“I can believe that easily enough.”

“Not for the reason you mean,” said Coyote. “I’m not at all embarrassed, I don’t feel guilty, and like I told you already, I’m not even sorry. So I hurt your feelings and dented my image—that’s tough, RK. Now I want to explain, and I want you to listen, voluntarily, if possible, under force if it isn’t.”

“Go ahead, then!”

“It seems,” said Coyote with care, “that your people are suffering from two very large and serious misconceptions. I want to take them up one at a time, okay?”

“I have a choice?”

Coyote ignored him and went on. “The first one is this bit about having to hide the mindwives because they will be kidnapped if their existence is known, RK. That just isn’t true.”

“It is written—”

“I know. I know very well. It’s written in the Book of the Holy Path. RK, who wrote that book? Think a little. Men did, you know. Men, who were fallible and who did not know everything.”

“They were holy men, divinely inspired.”

“Divinely inspired, shit.”

“Shit?”

“Never mind. Term of opprobrium. Look, RK—at the time that that book was written, thousands of years ago, your people were fleeing from religious persecution. The universe was full of barbarisms, then; people had to live in terror of idiocies from other people. Things have changed since then.”

“You think so?” asked Bess. “Have you taken a good look at the culture of my people, Citizen?”

“Wait a minute, Bess,” Coyote objected. “I’m not talking about behavior within the Ahl Kres’sah society—I’m talking about this Big Bogeyman from the Inner Galaxies that’s supposed to descend out of the sky and steal all your pretty ladies. That’s something else—and it’s just not a real danger anymore.”

“You can’t know that,” said RK.

“I can, because I do,” said Coyote. “In the first place, since the mindwives are part of your religious tradition, it really isn’t necessary that anyone know very much about them. Through all the Three Galaxies the right to secrecy in religion, the respect for cultural taboos, is accepted. Only a few people, people in positions of trust, need even know that the mindwives exist. That’s point one. In the second place, there are exotic sexual delights beyond imagining or description in the Three Galaxies today. A new one no longer causes riots—it’s just not that important. Even if the worst were to happen, even if the full details about the mindwives had to be splashed in living color across the Galaxies, it still wouldn’t matter.”

“You’re wrong,” said RK.

“No, RK,” said Coyote. “I’m right. Listen, let me give you an analogy. In the ancient Bible of Old Earth, right alongside the commandments like ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ in the early books, there were all sorts of dietary restrictions, given exactly the same commandment status. They were necessary, at the time that they were written down, because there was no satisfactory method then for preserving food properly, for preventing food poisoning, for doing all the things necessary for dietary hygiene. But thousands of years later, long after none of that was needed at all, long after refrigeration was developed, people were still practicing this long list of ridiculous ‘commandments’ because they had turned up originally in a sacred context. This is exactly the same kind of thing, RK. The law about secrecy for the mindwives was absolutely necessary in the days when religious persecution still existed, when kidnapping was a reality, but such crimes have been unknown in the Three Galaxies for hundreds and hundreds of years.”

“Oh, Citizen,�

�� said Bess softly, “if only you are right—and I’m sure that you are.”

“I am,” said Coyote, and he poured himself another cup of coffee.

“Now,” he said, “that’s the first misconception. And that’s the smaller of the two.”

“The smaller!”

“Yes, RK, the smaller. The really big one you people are lugging around with you is the one about this dolphin-human mating, and how all of you will be destroyed by the rest of the human race for it, and blah-blah-blah.”

“Ah, Citizen,” Bess objected, “there I can’t go along with you. I feel that you are right about the other point, I know what the chances of the mindwives being kidnapped are and just how silly that all is. But about this other matter—since you talk of the Bible, I remind you of the laws on just this subject that are to be found there.”

“I know, Bess,” said Coyote. “But look—nobody cares any longer. In the first place, the merging of your people and the dolphin-people is so complete that no one would ever notice the difference between you and ordinary human beings, whatever an ‘ordinary human being’ might be. Those tiny gill-slits you hide so carefully are not only not the spectacular mutation you consider them to be, they are just short of invisible. And whatever made you people think that this was the only planet where there existed humanoid—different, but humanoid—native races with which mating took place? Not to mention the incredible changes brought about by adaptation to various kinds of planetary conditions. Lord, you should see some of the so-called ‘humans’ that are to be found in the peopled universe today! If the Ahl Kres’sah had not deliberately shut themselves up like pariahs—although I do agree that it was probably necessary early in your history—if they had not done that, and if tourists could come to Furthest as they go everywhere else, you would long ago have seen that your fears were ridiculous.”

“Is that true, Citizen? You are not lying, it’s not a trick?”

Coyote breathed a sigh of relief. That was the first sign that RK was beginning to listen instead of just sitting there in a state of blind rage. He was encouraged.

“No, RK,” he said. “I’m not lying. There are ‘humans’ who are almost indistinguishable from birds. There are ’humans’ who have manes like lions, and tails, and claws. There are ‘humans’ that are not even describable—you have to see them to believe them. No one pays the slightest attention.”

The silence around the table was so thick that it was almost visible. Coyote waited, wondering if anything more was going to be necessary.

“Citizen Jones,” said the boy, “if what you say is true, then my people are undergoing a cruel hardship that is totally unnecessary and stupid.”

“Exactly,” said Coyote, pleased. “That is exactly right. And that is why I said I was neither ashamed nor embarrassed or sorry about what I’d done. Your people must be told the truth, RK. They must not be allowed to continue in this isolated purdah state because they feel they have to do so—if they just prefer it, of course, that’s different. But otherwise, it’s all superfluous. They can move as freely and as openly about the Three Galaxies as any other member of the Federation. There’s just no need, none, for all these restrictions, and there hasn’t been any need for them for centuries.”

Tears pouring down her face, Bess fought to speak, but RK grabbed her hands and held them tight.

“Do you understand what this means?” he cried. “Do you know, do you see what it means?”

“It means freedom,” said Bess. “It means that we are no longer to be hidden and caged, Ahr.”

RK stood up. “Now,” he said, “now I am so strong that you couldn’t possibly stop me from leaving the table! Now I am going to go up to the roof and I am going to sit and think about all of this until I can stand being so happy.”

Coyote laughed. “I wouldn’t try to keep you now, RK,” he said. “I’ve said what I had to say and succeeded in what I wanted to do. Later I’ll tell you why I wanted to do it.”

“Don’t bother about it, Citizen,” said Bess. “I’ll go with him and tell him the whole thing.”

“Bless you, Bess,” said Coyote promptly. “That’s good of you, because I think I’m talked out,” and he watched them go off together, very pleased with his morning’s work.

When he went to his bed that night he found he had one task left to do, but this a pleasant one. Bess lay in his bed, free of her trappings of velvet and silk, in her own spare strong beauty of skin and bone, waiting for him.

Because he could not believe it he reached out and touched her, and found her trembling.

“I’m so frightened,” she said. “I can’t believe how frightened I am… for a hardened criminal I don’t do very well.”

He sat down beside her on the bed and stroked her hair.

“What can I do for you, love?” he asked gently.

“I want something.”

“Can you tell me?”

In a very small voice, she said, “Citizen, I would like you to show me what the other kind of love is like. I don’t have any idea, you know—would you teach me?”

Coyote held his breath, and thought about a lot of things he could have said, about how it probably wouldn’t be very nice for her the first time, especially with her conditioning against physical release, about how she might well be disappointed by comparison with the ecstasy she was accustomed to, about how it might very well actually hurt her.

And then he decided that he really had talked enough for one day, and he pulled his robe off over his head and lay down beside her.

“Yes,” he said. “I’d be delighted.”

And he was.

CHAPTER TWELVE

“No matter how inconvenient or unpleasant an illusion may be, if a man has chosen it himself and held it long enough, if he has built it up in sufficient detail and become accustomed to taking it into account upon every occasion, it will become precious to him and he will fight to maintain it in preference to even a pleasant truth. This is because it will have become one of the anchoring points of his mind, like the points which anchor the web of a spider, and to displace it will cause a shift in equilibrium for which painful compensation must be made. This is only a form of self-defense; nonetheless it inhibits growth.”

(from the Devotional Book of Tham O’Kent)

Bess sat beside him in the dark room, running the antiquated projector that he could not have managed without her, prepared to offer explanations when explanations were required, and otherwise simply pleasing him by her presence at his side. She had made a choice of several films which she thought would give him a generally accurate conception of the Ahl Kres’sah culture and customs, the last customer had left the MESH for the night, and all was almost right. Coyote forgot sometimes that the girl who pleased him so was a condemned criminal, under sentence of Erasure; try as he would he could not make it seem real.

“This first one, now,” she was saying, “is one of our classic films. It’s a love story… the couple fall in love, and then they are separated when the boy’s family is called for Surface Duty.”

Surface Duty? The capital letters had been unmistakable. Coyote wondered, but decided to wait.

“It’s a bit trite and dated,” said Bess, “but it’s one of those things that everyone sees several times as he is growing up, and that becomes really part of you. That’s the kind of thing you need, isn’t it?”

“Exactly.”

“This should make a good beginning, then. It starts in a little village, called Saad Tebet; there’s no Panglish equivalent for that, I don’t think. You won’t be able to understand it at all, I’m afraid. I’m sorry about that.”

“Why not? My Furthester isn’t fluent, but it should handle film dialog, Bess; at least for the most part it should.”

Bess chuckled. “Did you ever try to talk underwater, Citizen?”

For a moment he was puzzled, and then he saw it.

“My god,” he said, “that should have been obvious even to me, but I never th

ought of it. How do you communicate then? Telepathy?”

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “Telepathy among our people is confined almost entirely to mindwives. We use a finger alphabet, and a set of gestures, when we are at home.”

“When you’re at home. I see.”

“The easiest thing, of course, would be for me to just translate it for your mind, but you don’t do that very well either; you’d miss most of it. I’ll just try to interpret it as it goes along.”

“Good enough, Bess.”

“Now—there’s the beginning. That’s an ordinary street, on an ordinary day. The ordinariest of the ordinary.”

On the pale stone wall the colors suddenly leaped to life, in old-fashioned two-dimensional projection. There was water, and a sort of stone corridor through which it flowed, and people, both men and women, swimming along as easily as any fish. They were naked, except for the broad bands that tied back the long hair of the women. Some carried net bags as they swam, others had small satchels on their backs. Several children swam by, darting in and out among the adults, obviously playing a game of some kind.

“What are the colored circles on the corridor walls, Bess?” he asked.

“Those are doors. You see the little disc at the side of each? That is like a doorknob—you push it and the circle swings round on a central pivot to let you in. All the homes of the Ahl Kres’sah have that sort of door, and the colors are traditional, very bright so that they can be seen in the water.”

“Those are Ahl Kres’sah homes? But what about the houses here in the city?”

“Oh, those aren’t real, Citizen!”

“Bess, that doesn’t make sense.”

“What I mean is, those houses were built by the ancient Elders who first settled this planet. When the requests first began to come out from the Inner Galaxies for statistics and information about our people, we built those—exactly enough. One city, one town, and one village. No one would ever live in them by choice.”

Furthest

Furthest