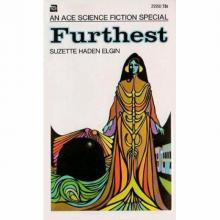

- Home

- Elgin, Suzete Haden

Furthest Page 4

Furthest Read online

Page 4

The letter began: “To Coyote Jones, beloved of all of us at Highmountain. Last night our teacher and friend, Tham O’Kent, left us. It was his wish that the Change take place in our ashram, and that we all be with him; he left us without pain or any sign of fear. We shall miss him greatly.”

Coyote stopped and looked up from the letter, afraid that he would cry and very much aware that Tham O’Kent would have laughed at such a reaction. It was only another evidence of how far away he was from the Maklunite Way that he could not look upon death as simply a change instead of as the end of things.

“Tham O’Kent had a message for you,” the letter went on. “He asked that we tell you that it was one of the sorrows of his life that all the good will and work that both of you put into your time with us was not enough to make it possible for you to remain. He asked that we tell you that it was not your fault, any more than it was his, but that there are people who are not ready for our Way. He said that perhaps you are kept back because you are needed as you are. And he sent you his love, as teacher and as friend.

“You know that it is our custom to keep all things in common, and that when one of us comes to the time of Changing, all those things that he has by him at that time continue to be held by all. However, it was Tham O’Kent’s request that his devotional book be sent to you, and we are happy to do so. Use it in wisdom and in love.

“We all think of you and love you. Tessa sends you greetings from Chrysanthemum Bridge. Return to us when you will.”

Coyote put the letter down gently and picked up the book. He was having a certain amount of trouble seeing it, but he would have known it anywhere, by touch alone. He held it tightly and fought the tears that threatened to make a fool of him, and then he saw RK standing quietly in front of him.

“You are troubled, Citizen,” he said gravely. “Is there any way that I can help you?”

“I’ve lost a friend, RK,” said Coyote past the lump in his throat. “I’ve lost a friend and I’m having trouble accepting that fact with regretful serenity, as I am expected to do.”

“Lost him, Citizen?”

“He is dead,” said Coyote harshly. “The Maklunites would say that he is only Changed, but I say he is dead, and the world is a worse place for his absence.”

RK sat down beside him on the steps and regarded him gravely.

“Is it all right to talk?” he asked.

“Oh, yes,” said Coyote. “Yes. It might even help.”

“I was wondering,” said the boy. “What are they?”

“What are what?”

“What you were saying, Citizen. Maklunites?”

“You don’t know what Maklunites are?”

“No. Are they people?”

“They’re a religion, friend.”

“I’ve never heard of them.”

Coyote was amazed. “How can that be, RK? Do you read the news MFs, watch the newscasts? They’re the most numerous religion in the Three Galaxies; only Ethical Humanism and Judaism have more people.”

The boy shrugged. “Perhaps I have just not paid careful attention, Citizen. What sort of a religion are they, these Maklunites?”

“A very gentle one. They live together, sharing everything; they love each other deeply. There is no closer being-together in all the Three Galaxies than that practiced by the Maklunites.”

RK was frowning. “They are communists, then,” he said severely. “Is that right?”

“Not communists,” said Coyote. “Lovers.”

RK looked shocked, and Coyote hastily amended his remark.

“Lovers of one another,” he said, “in the highest sense.”

“We are taught by our elders,” said RK, “that communal living is a deadly sin, and that it was meant that each man should live with his family and protect them and love them only.”

“You have every right to your beliefs,” said Coyote reasonably. “They are held by many peoples, you know; for example, that is one of the doctrines of Judaism.”

RK looked at him, a long measuring glance, and clasped his hands behind his back.

“Are you a Maklunite, Citizen Jones?”

“No,” said Coyote. “I tried to be, though. More than I ever wanted anything else in all my life, I wanted to be a Maklunite. I tried so hard, and many fine people tried to help me, but I was not able to do it. It’s one of those people who is dead.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Yes… well, there’s no help for it. Does it frighten you to find yourself sitting beside a sinner?”

He was half joking, but RK took him seriously, and appeared to be struggling with the problem.

“You don’t look like a sinner,” he said finally. “It makes it difficult to answer your question.”

“How would a sinner look?” Coyote asked in amazement. “Is there a special appearance for sinners?”

“Yes, there is,” said RK calmly. “They look miserable. Completely and totally miserable.”

Coyote whistled.

“RK,” he asked suddenly. “Do you really believe that?”

“It is not possible,” the boy said with the steady tones of unshakable conviction, “for a sinner to be happy.

“The Maklunites are happy,” said Coyote. “They are the happiest people I know.”

“I can’t accept that,” said RK. “If they live as you say, they cannot possibly be happy.”

This, Coyote could see, was not going to get them anywhere. The boy was spouting some sort of cant doctrine, and it sounded like a dangerous one and one of which he should be disabused. On the other hand, Coyote could not afford to make an enemy of his only human link with the Furthesters just for the sake of a religious or philosophical argument.

“Well,” he said, standing up, “this is an interesting discussion, but we’ll never get anything done this way, will we? Let me put up my mail and we’ll get started.”

RK seemed relieved to have the subject changed, and he went to work willingly enough. Coyote took the Devotional Book and laid it away carefully in his room, taking time to look for a few seconds at the well-used pages carefully filled with Tham O’Kent’s meticulous writing, and then he went to join the boy. They had a great deal of work to do.

“From Coyote Jones, with love to all of you at Highmountain:

“I received your letter yesterday morning, with the book enclosed, and I thank you with all my heart. This is the first moment I have had free to write to you.

“I know that there are many of you there at Highmountain for whom the teachings in Tham’s devotional book were of great importance, and you must have had a feeling of sadness at seeing the book leave your cluster instead of taking its place upon the shelves in your ashram. I am touched and honored, both at the tenderness of the sacrifice and at having the book for my own. (I can hear you laughing at that phrase, ‘for my own,’ but I suppose it will surprise none of you, knowing me as you do, and it is the most natural for me.) I will treasure the book until the time comes that I can pass it on to someone else, and I thank you again. If at any time you should have need of it, you have only to send me a message and I will return it to you.

“As you probably know, I am now operating a MESH on the planet called Furthest; I find the job very normal-seeming, but the planet is strange. My MESH opened for the first time last night, and I would like to tell you about it, except that I’m not very good at expressing myself. Perhaps if I just tell you about one of the ladies—and I use that term deliberately—you will be better able to imagine the rest.

“Try to imagine a young woman, very tall and thin, with skin the color of pale copper. She is wearing a gown that covers every inch of her from the top of her throat to her feet, and you can see nothing of her but her head and her hands. The gown she wears is of heavy synthetic velvet and is vertically striped in alternate dark and light green. The collar is as high as it could be without choking her and the sleeves come down in points over the backs of her hands almost to her fingers. The skirts of

her gown are fully a yard around and sweep the floor when she moves. Around the collar, the border of the sleeves, and the hem of her dress, there are three rows of heavy golden braid. She must be wearing something on her feet, but they are hidden by the gown, so I don’t know what it could be. Her long brown hair is caught at the back of her throat by a loop of the golden braid that trims her gown. She wears no cosmetics of any kind, unless I simply am unable to detect them because of the skill with which she has applied them. Over the top of her head there is a band an inch wide, of the striped synthovelvet, going down the sides of her head and attached to what look like velvet earmuffs, heavily trimmed with pearls and gold lace, over her ears. (If you aren’t familiar with earmuffs, they are a kind of round covering for the ears, attached to a band over the head, and worn to protect the wearer against severe cold. It doesn’t ever get very cold here.)

“Now multiply this lady by fifty, pair her off with men who are just as incredibly dressed, except that they wear full trousers instead of skirts, caught tight at the ankles, and you will have some idea of the appearance of my opening night audience. There were no children present, not even one, but when I have seen them, they were dressed like their elders.

“Usually, you know, the opening night of a MESH is a very festive occasion. Everyone knows that it is a place for all the people in the area and there is always a lot of sharing, a lot of helping, and people come in to the opening warm and loving and ready to know one another. Not here, let me tell you. These people not only do not know how to act in a MESH, they’ve never even heard of such a place. Apparently their government has carefully censored such information, along with a great deal of other information, although there couldn’t be any formal official policy against MESHes or they wouldn’t have allowed one to be opened here. At any rate, the people came in hesitant and half-afraid, and in spite of everything I could do they stayed that way, wandering around in twos and threes, touching things as if they had poison spines on them.

“I let that go on as long as I dared, hoping it would get better of itself (which it didn’t) and then I called them into the central area and sang to them. And that was the strangest thing of all. You know that I have almost no ability to receive the thoughts of others; like a twentieth-century primitive I get only blurry images and emotions instead of the clear information that normal people receive. But I have never faced opacity such as this before. There were perhaps a hundred people there, and they were like a hundred small squares of flat blackness, or black flatness. Just nothing. Emptiness. Total closedness. I wasn’t getting messages of dislike or fear, there was just nothing there at all, and that’s not normal. It was as if every single person in the Mesh was under orders to maintain an automatic and total psychic block at all times.

“I can’t imagine what could have caused a whole people to be like that. It couldn’t be accidental, they would have had to be systematically trained. It must be some part of their prudery code, something that is a part of ‘good manners’ for them, some part of their training for public behavior. Surely they can’t be like that always, even when they are at home with their families.

“I don’t mind admitting that I was awfully uncomfortable, and I wasn’t sure exactly what to do about the whole thing. I decided that the best place to start was with the idea of building up confidence in their minds. So along with the music last night they got a constant full-strength mental dose of trust me, i am a good man and i am only here to help you. I kept that up for two solid hours, until my whole head felt like a bruise, and it still aches, but I hope it did some good. I could sense no change in them (although it would have to be a pretty damn radical change, of course, before I would sense it). But when they began to leave they all came up and spoke to me in a friendly enough manner, so I suppose I should be satisfied with the results for the time being.

“They appeared to be completely mystified by the music I sang and played, but that’s nothing unusual. People ordinarily are mystified by the new and strange, and apparently these people have never been exposed to any sort of antique music. They did seem interested and I think that that interest will draw them back here so that I can try to reach them more effectively. I can at least hope so.

“I thank you again for the gift of Tham’s devotional book, and I send you my warmest wishes and my love, from Furthest…

Coyote Jones“

CHAPTER FIVE

“The idea that telepathy was in some way a freakish, non-human—or even worse, superhuman—ability disappeared only slowly during the twenty-first century. Difficult as it is for us to imagine such a situation now, it was at one time the accepted practice to ridicule and to discourage any and all attempts to use telepathy or” any of the normal human psibilities.“

(from A Brief History of the Human Race,

by Dr. Evelyn Margaret O’Brien, Ph.d.)

RK was uneasy and strange the next day, to such an amazing degree that Coyote began to worry. They were stocking MFs in the dispensers and checking them against the inventory strips, a simple job that should have been a matter of thirty minutes time. But RK was so distracted and half there that three times in the first quarter of an hour he agreed to an MF title that Coyote called out when he should have noted it as an error. By the time they should have been through, the inventory was hopelessly mixed up, and Coyote gave it up and called a halt. “Look here,” he said, “yesterday I was the one who was upset, and you did your best to cheer me up. Now this morning I would have to be an idiot not to know that you are troubled, and we’re not getting anything done. I think it might be better for the business if we took a break and tried to fix your problem.”

The boy flushed, and Coyote felt the curious sensation that meant a blocked mind was opening, a sort of slippery sensation behind the eyes, as if something had broken the surface of some hidden water, and then it was gone. He sat down beside RK and waited, not wanting to push him. He could have done some mental pushing, of course, but he hesitated to do that. It was almost always safe to operate mentally with large crowds, because the facts about mass telepathic manipulation had been carefully suppressed, and in fact a number of articles had been written recently doubting the very existence of any such technique. And to be absolutely accurate, the existence of a skill held by only thirteen persons in three galaxies almost constituted non-existence. But if he were to attempt to project to an individual, at such close quarters, he ran the risk of having that individual become alarmed at the strength of the projection, and that kind of alarm would inevitably lead to trouble. He wouldn’t risk it unless it appeared really necessary, and settled for. holding in his mind a vague sort of reassurance concept, reasonably sure that the boy would not spot it as projected.

“Citizen Jones.”

“Yes, RK?”

“I do have a problem, you know that? I’ve got a really awful problem.”

“Maybe I can help you, if you’ll let me.”

RK stared at him gravely. “You would, wouldn’t you? I know you would. The only thing is… I feel like I ought to be able to trust you, but I have always been taught―”

“That offworlders cannot be trusted.”

RK nodded.

“Well,” said Coyote reasonably, “you’ll have to decide that for yourself. Are you telepathic? You could check my thoughts for evidence of evil intent, RK; I’d be perfectly willing to let you.”

The boy went white, and Coyote knew he’d goofed. Apparently he’d touched some taboo area.

“What is it now, RK?” he asked. “Have I offended you?”

“You asked if I was telepathic.”

“So?”

“Of course I’m not telepathic! Why would you—why do you ask me that? What made you think of that question?”

“RK, you’re really frightened—why?”

“I’m not frightened.”

“I don’t believe you. You’re shaking.”

“That’s not true!”

“RK,” said Coyote patiently, �

�I’m sorry if discussions about psibility are taboo for your people. I know your police use telepathy, and I didn’t realize it was a subject that one doesn’t discuss. It was just an error of manners, and I won’t mention it again. But so far as your problem is concerned, you are going to have to decide for yourself, like I tried to say before, whether you can trust me or not. If you can’t trust me, then nothing I say to you is worth anything anyway. If I’m not trustworthy I can sit here all day and swear I am, and it won’t mean anything.”

RK dropped his face into his hands and moaned in sheer misery, and Coyote began to feel genuinely concerned. Apparently it was not just a minor problem.

“Try to trust me,” he coaxed. “Try—you should know that you can.”

Yow should know, he thought, because you were here last night all evening long while I was putting out that trust-me stuff.

RK drew a long shuddering breath and raised his head.

“I’ll have to trust you,” he said simply. “There’s no other way. Only I’m going to have to ask you to trust me, too.”

“Of course.”

“I’m going to ask you to do me a favor, but just on trust. With almost no explanation. If you won’t do it that way, then I’m up against it.”

“Try me.”

RK went and stared out of the front window onto the street, and Coyote waited. He had found waiting one of his most useful talents over the years. He only wished the Fish had just a little scrap of that particular talent, however; his report about the empty citydome had brought down a flock of URGENT notices on him from Mars Central, as if the inner secrets of a totally anti-social people could be brought into the light by shouting and shoving. He was waiting, and would continue to wait as long as he dared.

“Citizen Jones,” said RK from the window, “it’s not for myself that I am asking the favor. It’s for my sister.”

Furthest

Furthest